This blogpost was prompted by a Twitter conversation regarding the release of the recent All-Party Parliamentary Group on Data Analytics report Our Place Our Data – Involving People in Data and AI-Based Recovery and the need to have a more localised approach to developing data and AI ethics policy.

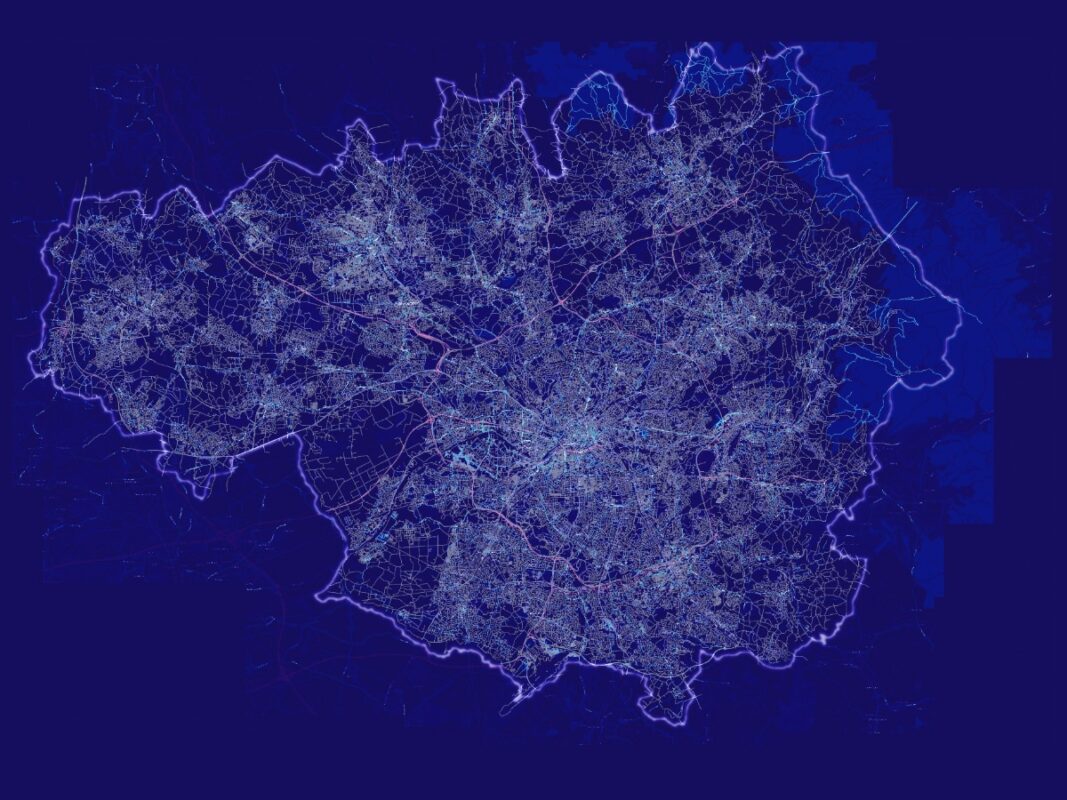

For the past two years, Open Data Manchester has been developing the Declaration for Responsible and Intelligent Data Practice – which sets out 23 principles for how organisations in Greater Manchester can develop their data practice for the benefit of everyone.

Ethics play a big part in the Declaration and many of the principles ask signatories to consider the ethical implications of their decisions.

But the challenge of ethics is – whose ethics?

Ethics ask you to make a personal assessment of a situation, grounded in a moral or philosophical framework, of which there are many to choose from.

You only need to look at some of the classic ethical dilemmas to understand that different frameworks will lead you to different outcomes…

Consider the ‘trolley problem’ – is it better to kill one person to save many? Or, Kant’s ‘axe man’ – who will kill your friend if you decide to be honest when asked if you know where they are.

Ethical decisions are context dependent and, just as there isn’t a universal ethical framework, these contexts aren’t universally experienced, understood or shared.

Centralised frameworks, local communities

This presents a challenge when we look at local-service provision – where understanding of context is critical – and solutions that are tailored to the needs of local communities are essential.

When developing the Declaration, some voices in the local public sector told us that they were under increasing pressure to innovate, including using data and digital technologies to maintain services, without fully understanding the ethical implications of doing so.

There seems to be a growing awareness within local public- and voluntary-sector organisations, especially in Greater Manchester, that ethical decisions need to underpinned by local context. Initiatives such as the GM Responsible Tech Collective have spent good time and energy seeking to address issues like this.

But most of the ethical tools and frameworks being developed are through well-funded, and crucially, centralised organisations.

That means, of course, they often won’t have the ‘on the ground’ know-how of local, public-service delivery – but also, they won’t have to experience the local consequences of badly applied decision-making technologies – which not only cause people harm, but also erode trust in all decision-making.

Centralisation also leads to the accusation that any ethical frameworks that are developed lean towards the needs of national government policy, over those of local communities.

Localised ethical frameworks for building trust

There is a lot of great thinking being developed in this area by organisations such as the Ada Lovelace Institute, Alan Turing Institute and Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation.

At ODM, we want to ensure that ethical frameworks for local, public -service delivery are firmly situated in the localities being served.

Ethical decision-making processes must be designed to engender trust and confidence in the decisions being made, by being sensitive and relevant to the concerns, needs and desires of local residents.