The Open Product Initiative is a collaborative project between Loughborough University, Open Data Manchester and Dsposal, with support from TechUK and Buyerdock.

The aim is to explore the development of an open standard for batteries and (waste) electronic and electrical equipment (W)EEE data, building on the work already conducted to develop the Open 3P standard for packaging data. Whilst there are significant differences between packaging, EEE and batteries our hypothesis is that the structure we have developed for the Open 3P standard, which builds from base materials to materials, which get turned into components which get combined together to make complete packaging, could be applied to (W)EEE and batteries without many changes to the structure. That is, base materials make up more complex materials, which get turned into components/parts which get combined together to make complete products.

For open standards for data to be of use they must accurately reflect the reality of the system and actors they represent. To begin to engage with stakeholders in this space we ran an initial round of online workshops in May 2024 which were open to anyone interested in the (W)EEE and batteries ecosystems, and a second round of workshops in July. We also spoke with the members of TechUK at one of their meetings and held a couple of one-on-one conversations.

The May workshops were attended by 10 stakeholders, mostly from a compliance background, but also consultants and reuse organisations. The July workshops were attended by 9 stakeholders, some of who had attended previously, with new engagement from some manufacturers, distributors and retailers.

Whilst these conversations were extremely informative, we are very aware that we are missing the voices of many more key stakeholders and as the project continues we’re keen to ensure we engage as many of these as we can.

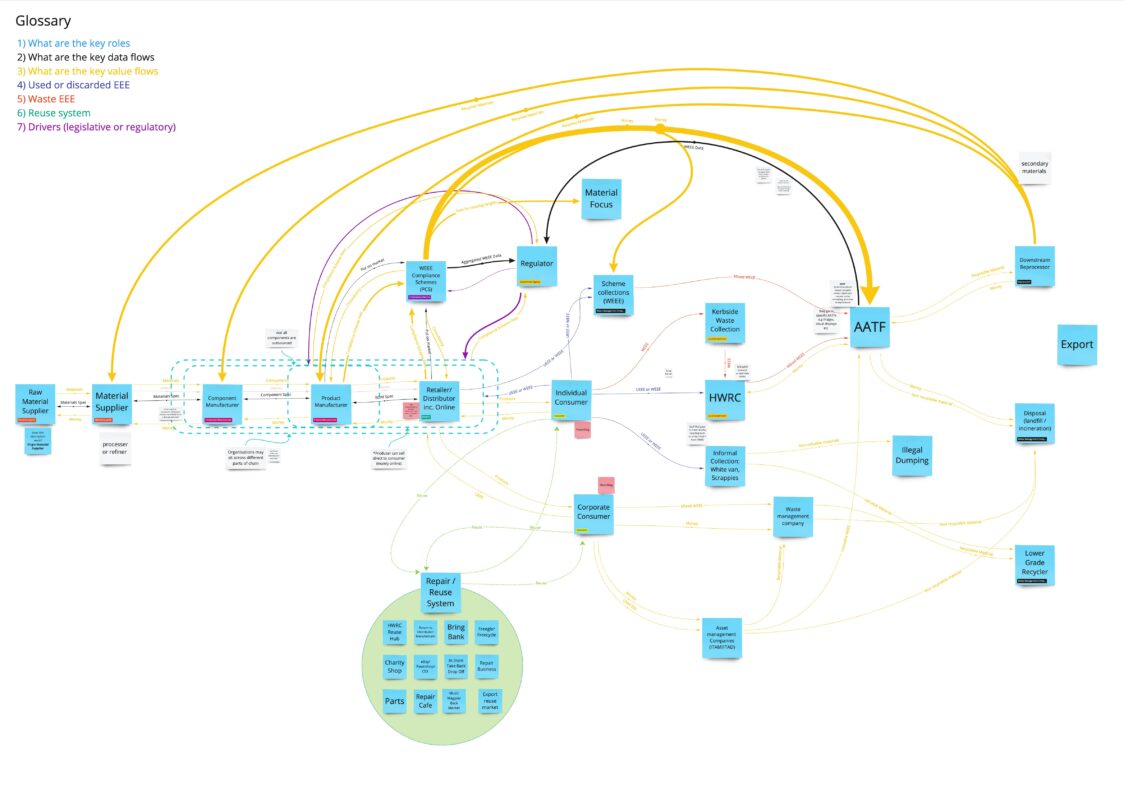

When working in a new sector we find there is a lot of value in developing an ecosystem map alongside stakeholders. It allows us to visualise and map out the different actors, systems, connections, and value flows (whether that is money, data, products or services) as well as drivers (such as regulation) and blockers.

Although we had initially thought we might do a combined ecosystem map for both batteries and (W)EEE as there is a lot of overlap it was clear from the research that this wasn’t the right way to go. What we have at the moment is a (W)EEE map as we have not yet engaged with many stakeholders with battery sector knowledge.

A few key things we learned from the ecosystem map:

- It’s an incredibly complex landscape

- Actors can often inhabit more than one step in the chain e.g. They might be a component manufacturer and product manufacturer, or they might be a distributor and offer repairs/resale and recycling

- Products can sit in parts of the value chain for years or decades. And hoarding of EEE is an issue for the industry as it leaves valuable resources stranded in drawers and cupboards which could instead be reused or recycled

- That products can circulate around actors and easily end up in the informal economy and this can be a problem for the regulated industry as it can be hard to get the data and even if the data does exist it can’t be counted towards the WEEE reporting and targets

- Reuse, repair, refurbishment and resale happen a lot and are very hard to measure (and need their own map)

- Whilst data is being shared and reported, though typically at a high level, there are parts of the ecosystem which are like blackholes for data and from a reporting and compliance perspective this causes significant challenges and costs

We also explored assumptions and knowledge in the workshops. This can help to identify areas that need further research by highlighting things we don’t know and things that lack evidence. It also helps to clarify what is known and to surface particular challenges. One such challenge was that of the growing ‘fast-tech’ sector – that’s basically the equivalent of fast fashion but with electronic and electrical equipment – with products being brought to market that are designed for disposability. There was also discussion about the prevalence of adding ‘tech’ to non-EEE items such as LEDs on clothes or packaging. In both instances this leads to valuable minerals and metals being lost through improper waste disposal and recycling.

This disconnect between product designers and manufacturers and the end of life fate of their products came up repeatedly. Poor understanding of the recycling process and infrastructure can lead to products flooding the market which are extremely hard to deal with once they are discarded as waste. This ranged from the now infamous disposable vape (which have caused significant issues in UK waste management namely through littering and causing fires in bin trucks and waste facilities) to high end products like new iPhones made with titanium when there is no mechanism to extract that in the current UK infrastructure. Discussion was also had around the ways in which certain additives, especially those falling under persistent organic pollutants (POPs) or substances of very high concern (SVHC) can lead to huge disruption in recycling or reuse.

Improving communication and collaboration between different parts of the value chain was identified by some attendees as a way to overcome some of these issues. At the one end this could help designers and manufacturers consider end of life (and certainly that is one element that the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) is looking to address). At the other end providing the waste sector with foresight of new products before they’re being dealt with as waste so processes and infrastructure could be invested in to deal with new product types, materials or disruptors could see more WEEE going through higher quality recycling and recovery processes where more of the valuable materials are captured.

Many stakeholders talked about how better data about products could support sustainability initiatives and a move to a more circular economy, but there was also concern about the burden increased reporting and data had on the industry. Some attendees did also raise concerns that for some AATFs (approved authorised treatment facilities – recycling sites specifically approved for treating WEEE) detailed information about products wouldn’t impact on their processes as it would be too time consuming and inefficient to identify and segregate particular items, which raised questions about how much value a digital product passport (DPP) may provide for this end of the chain.

There were worries that the increasingly widening scope of some DPP initiatives risked letting perfect get in the way of good and there was a desire for a more pragmatic approach. This was certainly evident in our July workshops when talking through the types of data that might be included in an open standard for EEE and batteries. It was clear from all our conversations and workshops that while many are supportive of DPPs and can see the potential benefits of better data sharing across supply chains, that this must be balanced with what is achievable and meaningful. Data should be shared where it can have a positive impact on outcomes, not just for the sake of being shared. With sustainability rightly high on the agenda there is an increasing requirement for more and more environmental reporting. As an organisation with ‘data’ in its name we are unsurprisingly advocates for how data can be pivotal in helping understand, monitor, prioritise and inform better policy, targets and decisions. But we also need to ensure that we don’t end up creating a culture in which all our sustainability experts are completely tied up with reporting with no time or budget left to undertake the actual work needed to shift the world’s economy to one which can respect our planetary boundaries. We believe open standards for data can help reduce the burden and unlock new opportunities and we’ll be continuing to explore how this might develop in the coming months.

Over the summer we’ll be drafting an initial structure for a new data standard so that we can share it with stakeholders for feedback and improvements.

If you’re interested to get involved sign up to one of our upcoming events or find out more by getting in touch.

For a more detailed look into the changes happening in the EU check out our other blog – The EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan: The Critical Role of Data and Open Standards