Earlier this month, Open Data Manchester welcomed three practitioners who care about people and place to talk about where data fits when we’re thinking about participation and representation of local people.

Sobia Rafiq is a co-founder of Sensing Local, which works across India to help people fill big data gaps that can often lead to bad policy.

Ellie Cosgrave is director of research at urban design agency Publica, as well as associate professor of Urban Innovation Policy at University College London.

She has weaved feminist action and activism through her career and is currently leading Publica’s work on increasing gender inclusion in London and beyond.

Toyebat Adewale works in user research and community engagement for Open Data Manchester, working on the Right to the Streets project in Trafford, Greater Manchester.

This project is working to understand people’s experiences and perceptions of where they live in order to reduce violence against women and girls, and create inclusive and active streets.

First up, Sobia Rafiq outlined one of the key challenges facing many communities. “There is a scarcity of data,” she explained. “We start literally from nothing – and this is the reality in most cities in India, even though you may have a large amount of city-level data.

“It’s not comprehensive, it’s not accurate, usually resulting in misinterpretation of what the local needs are, mismatched priorities of decision makers and the beneficiaries, as well as a lot of top-down decision-making that tends to be largely intuitive.”

Democratising planning

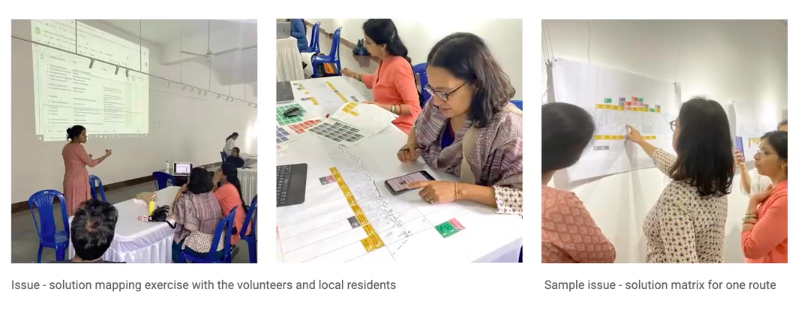

In order to tackle this, Sensing Local has worked at the city level – getting more than 1,000 volunteers over a few months to help validate data for the first-ever solid waste management database for officials in Bangalore; at the ward level, where 10 people over two weekends can fill a data gap about the needs or experiences of tens of thousands of people; and at the smallest street level too.

Most recently, Sensing Local’s Walkable Bengaluru project has supported more than 200 volunteers to audit more than 300km of roads and paths so the city can prioritise the ‘walkability’ of these routes.

More than a third of journeys in India are taken on foot, and there is significant air pollution, obesity and costs for other transport options, but there’s not enough money to fix every street.

So volunteers work in pairs to review physical barriers, such as construction works or debris, footpath quality and challenging junctions in sections of streets of 500m to 700m – each one taking just three hours.

“It does not take long to bridge that gap,” Sobia emphasised.

Because there are areas with no internet connection, the app for volunteers to upload their reports uses GPS and the project is loaded before people leave to collect data. It is synced when they arrive back for a workshop and can then be found in a live dashboard.

Each area gets a report card, with issues found, solutions to these problems and the costs of fixing them, all brought together in deliberation with volunteers, which then enable the city to easily allocate budget. She emphasised herethat it’s not just about the data – the government needs to be able to act.

“We never thought that not having a vendor policy [for people selling goods] could actually be the biggest inhibitor to actually having walkability in the city. So we may have infrastructure, but everything is encroached and management of encroachment is not happening, because there’s no policy.

“So in some way, we get aspects that are quite unrelated right now in the minds of the government. But if you start looking at it from the perspective of solving for walkability, it’s extremely related and almost an urgent issue to solve.

“Similarly, we were able to identify roads and footpaths that require very minimal interventions and budgets to get changed into something that is doable. Again, this has been something that’s been hugely beneficial because the approach of the government has been that we redo every road from scratch, spending a tremendous amount of money, which is actually not required.”

“It’s extremely reassuring that so many people do want to spend their weekends to come and improve aspects in their own city and add to the data for the city,” she said.

Speaking to Sobia’s presentation, Ellie called it “community power, providing on-the-ground, democratised lenses, literally asking people to show us how they see the city and being able to then convene that for collective power with decision makers and make it accessible and practical, and enabling policymakers to make good decisions, rather than being always adversarial. Although I think there is room for that as well.

“You made it look quite straightforward… a simple, logical piece of work, but I think it’s radical. And it’s really complicated.”

Ellie’s work focuses on gender inclusion in public space and, setting out the context of the challenge, she said: “Growing up in a city, I understood immediately, as a young woman, or even a girl, the ways in which presenting as female made me vulnerable to male violence, and limited my access to free and full participation in urban life.

“Having said that, I grew up in London, and I love the city. I have always felt that the city has been my home, as much as the inside of my house. The city was a place in which I was able to see my friends hang out away from parents. It was a place I was able to protest.

“And so I guess my whole life and work has been about this, this kind of tension between the freedom and opportunity and liberation that the city has, as well as understanding the ways that my vulnerability is contingent on my gender.”

Increasing belonging

She pointed to issues with how police and crime data does not make visible the many ways women may feel unsafe in a city. We don’t see those longer routes home,” she said. “Much violence against women and girls across the world is not in fact illegal. It’s not illegal to follow a woman home. It’s not illegal to shout at her in the street… and [even] the more serious crimes are not reported and are certainly not prosecuted. And so those kinds of datasets are not working to reveal the lived experience of people”.

She emphasised that “a sense of belonging, and being able to participate in one city in one’s urban development processes is actually one of the most important factors of feeling safer in the city… particularly from a gender perspective”.

Publica is currently working with the Mayor of London on a series of projects developing principles and tools for gender-equalising public space – with a new toolkit released online that includes 10 questions you can ask yourself throughout the lifecycle of a development project.

Publica has supported Wandsworth Council in London on its first Night Time Strategy, where Ellie’s team worked with six local residents to understand their experiences of their area after dark, initially by asking them to record the sounds of their neighbourhood.

She was interested to find the word ‘dark’ used to describe places like underpasses even when they were well lit – as a euphemism for ‘unsafe’.

Speaking of a mother and daughter involved with the work, who had a negative relationship with the area at night, Ellie said: “Through being part of a conversation that was meaningful with the local council, they described that suddenly her daughter was pulling her out of the door in order to go and record sounds after dark.

“And so a big learning from that, to me, is that it is not necessary even for the city to change in order for people to feel safer in it. Participating in in telling your story, and working together, transforms people’s experience of places.”

In Waterden Green, East London, Publica has supported a group of girls to become “clients of their own area” so they can employ an architect and design a brief for a public realm project.

“We didn’t really need to train them because they were phenomenal already. They know exactly what they want. They know the complexities of the issues. And it’s really just a case of the planning authority handing over power to people who are going to use it, own it, live in it, and to be the custodians of the next generation.”

In nearby Blackhorse View, women and non-binary people were asked to tag their local area with simple red or green spots to give them a playful way to describe their experiences of the space.

“Within about 45 minutes of a conversation with people who are not experts in urban design, but who are experts in their own lives and lived experience, I found so much. We covered everything I know, and then a lot more nuanced and new ideas that I had not heard in 10 years of working on gender inclusive public spaces.

“Again, it shows to me that communities already understand, already know, the ways in which their built environment can be improved, where the problems are, and have really nuanced perspectives, if only we took them seriously. And if only they were understood and acted upon.” Here she pointed back to Sobia’s focus on about making actionable recommendations to local authorities.

In Trafford in Greater Manchester, Publica has developed a card game to help women and girls have better conversations about safe streets. And in Earls Court, London, a Public Realm Inclusivity Panel was asked ‘what it means to belong’ – and what they imagined included time travel and dinosaurs.

But Ellie explained: “What we really wanted to do was to support them in stretching their imagination about what is possible and tell stories about what they want their future place to be. We wrote up their stories into cartoons that signify a desire that they were really getting to the bottom of and then a key recommendation to the development company about what needs to change.

“So we ended up after, over an hour-and-a-half workshop, with a lot of really practical recommendations that were born out of imagination and what they wanted for their space and place.”

Toyebat Adewale has been working in Trafford since October to develop a project that similarly helps local women and girls talk about safety, activeness and belonging.

In partnership with Greater Sport, Publica, MIC Media, Trafford Council and Diva, the team designed three-hour walkabout workshops that mapped routes people would avoid and places they like to go.

There were 14 sessions in five geographical areas or pockets within Trafford with 56 people, supported by conversations with a further 55 women and girls, and a survey.

Empowering people

Through this, they noticed the importance of Chester Road, which is a key route into Manchester, but where Toyebat said “pedestrians, people who use the streets, are seen at like the bottom of the ranking because this road then divides the community and [there are] poor crossing facilities for people to get to and from”.

Lighting, as in London, was another key theme, though people were less worried about poor light the more familiar they were with the area.

“Everybody loves a park and like an open space, but then also being able to see people who are smiling and looking at you, or will welcome you,” Toyebat said. “So that sense of feeling, adding onto your experience and enriching it.”

These themes are being built into a ‘place audit’ which Toyebat said will mean “individuals and communities can use it as a tool to advocate for change and prioritise tasks”.

“Because we’ve used the language that they’ve used, it’s more relatable, but then it has the backing of an audit,” she added. “Not everyone at higher levels respects the kind of anecdotal or quotes that you have from individuals. So sometimes you just need that extra resource or tool to help your voice be heard. But then when you do it yourself, that’s quite empowering, which is what we’re trying to create.”

People produced individual maps of places they liked or didn’t like. “One said it wasn’t nice for match days [football matches], or there’s lots of car traffic, and a sad face… one participant just put smiley faces on areas that made them feel like they belonged. So it’s good to have like the variety and the different lenses that people look through their space.”

This will be brought into a master online map where there will be an overlay of ‘hotspots’ where people like enjoy going or want to avoid. This can hopefully be compared to crime data of the area to highlight the “difference between experience, perception and what is reported and what is not”.

Data and Policy is an occasional series run by Open Data Manchester looking at the development and application of data practice in the development of public policy.